Windows Access Tokens

As I was reading about an IcedID campaign, I came across a privilege escalation technique I was unfamiliar with: access tokens. This post is my research into the topic.

What is an access token?

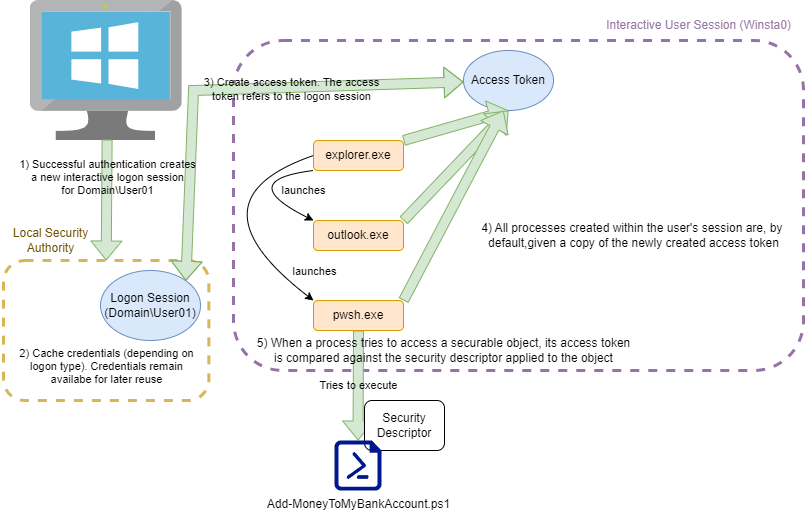

In order to make local authorization decisions, the Windows Access Control Model consists of two parts:

- The access token - describes the security context of a logged on user. Contains information such as their SID, group membership, privileges on the local system, and logon session

- The security descriptor - the authorization policy applied to an object. This policy is initially applied to an object at the time of its creation. The policy is an Access Control List (ACL), made up of Access Control Entries (ACEs), where each ACE identifies:

- A principal

- The desired access (read, write, execute)

- The authorization level (allow, deny, or audit the desired access)

When a user successfully logs onto a computer, a logon session is created for that user in the Local Security Authority (LSA) and a new primary access token is created. This access token is associated with the logon session stored in the LSA. Each child process or thread executed on behalf of the user is assigned a copy of the access token. When the process attempts to access a securable object (like a file, process, service, etc), Windows determines if the process can perform the desired action by evaluating the access token against the object’s security descriptor.

Side Quest: SeDebugPrivilege and Access Control Decisions

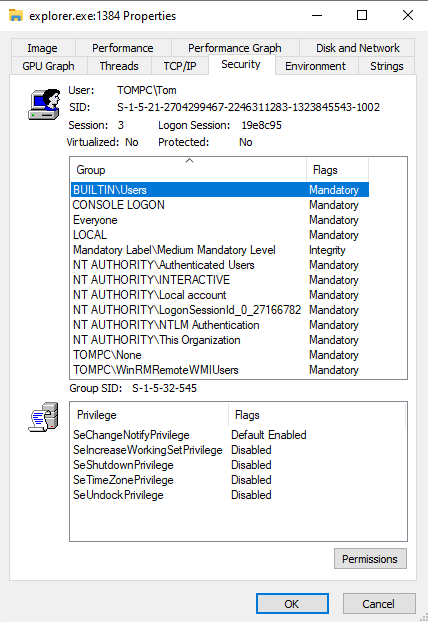

As a side note, if you've ever wondered by SeDebugPrivilege is so powerful, it's because it allows the holder to bypass the access control listed in the security descriptor and can open any process regardless of the discretionary access control list in the security descriptor (except for protected processes).Process Explorer can show a glimpse of what’s inside an access token by right-clicking a process and selecting the “Security” tab.

Not all of the information that an access token contains is shown in Process Explorer; some (but not all) missing properties are:

- Token type

- Impersonation level

- A template DACL. This is the default DACL that’s applied to any newly created securable object when the user doesn’t manually specify a DACL

- and more

As already noted, access tokens contain details about a users’s group memberhsip. Because access tokens are typically created during logon, any changes to a user’s group membership won’t be reflected in their current access token until they logoff and logon again.

Impersonation tokens

There are two types of access tokens (both of which contain the same information as described above):

- Primary - an access token that can only be assigned to a process. These are also referred to as “Delegation tokens”

- Impersonation - an access token that can only be assigned to a thread

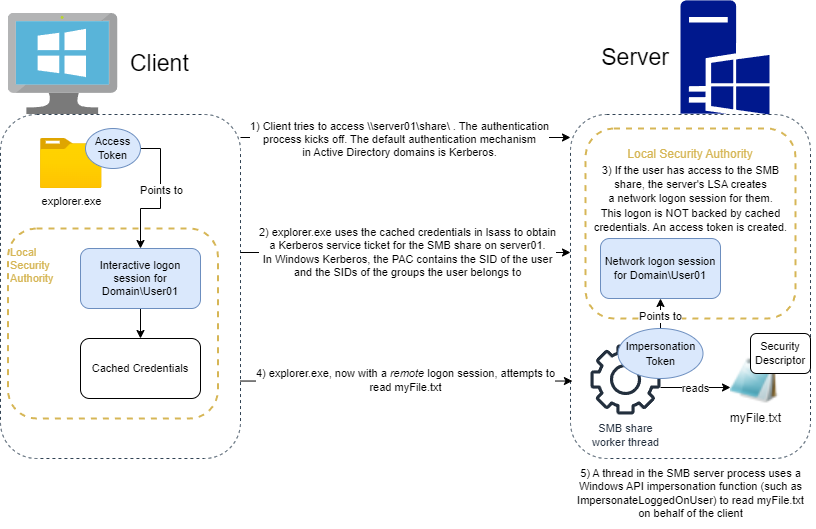

Impersonation is a feature in Windows that allows a server to create a thread that acts on behalf of a client connecting to it. A common example is a user interacting with a file on a network share. To determine if the user has the correct permissions to perform the desired operation (read, write, delete, etc), the server would need to know the user’s SID, the SIDs of the groups that user belongs to, and the security descriptor on the file. The user SID and group SIDs are all contained within an impersonation token that the server uses as it attempts to perform the requested file operation as if it was the user.

In an impersonation scenario, the primary access token will describe the security context of the server process (such as the account running a file share) while the impersonation token (assigned to a thread in the process) will describe the security context of a user performing a file operation on the file share.

If an access token is only used to make local authorization decisions, how does a remote server know what information to include in an impersonation access token?

Access tokens, domain authentication, and Kerberos, oh my!

Remember: access tokens refer to logon sessions stored in the local machine’s LSA, so an access token on a local machine cannot be passed to a remote computer. The user must first successfully log on to the remote computer (typically via a non-interactive logon done transparently by Kerberos in Windows Active Directory domains) to create a logon session. Then, the remote computer will create a new access token and associate it with the newly created logon session. This access token can then be converted to an impersonation token and used by the file server to impersonate the client.

In Windows Kerberos, the Privilege Attribute Certificate (PAC) of a service ticket contains the SID of the user and groups the user belongs to. This information is used by the remote LSA to create a client’s access token.

The image below illustrates impersonation tokens used in a client/server relationship

Abusing access tokens as an attacker

There are two primary ways access tokens are abused by attackers:

- Stealing an access token for another user to escalate privileges locally (either to

SYSTEMor another user account) - Changing the cached credentials associated with the current access token to point to new credentials

Stealing access tokens

The open source red team framework Sliver has the ability to steal access tokens from other processes (provided the user has the appropriate permissions) by using the impersonate command. This command eventually calls impersonateProcess which opens the process (OpenProcess), gets a handle to the process’s access token (OpenProcessToken), impersonates the user that owns the target process (ImpersonateLoggedOnUser), and duplicates the access token (DuplicateToken). The Sliver malware, or implant, can then utilize this stolen access token to run processes in the context of the target user and use the cached credentials associated with the target user’s logon (if the logon was interactive) to impersonate the user over the network.

There are two limitations to this technique. The first is the privileges required to perform the attack. The specific privileges required differ based on how the attack is performed, but all variations ultimately depend on privileges that are typically only available in an administrative context (high integrity level process)

- The sliver implementation requires

SeAssignPrimaryTokenPrivilegeandSeIncreaseQuotaPrivilege - Justin Bui’s implementation and the PowerShell Empire implementation only require

SeDebugPrivilege - This StackOverflow implementation requires

SeTcbPrivilegeandSeAssignPrimaryTokenPrivilege

The second limitation is the length of time the token is valid for. An access token is only good for as long as the associated logon session is valid. If you’re stealing an access token and the victim’s logon session ends, so does your access.

Changing cached credentials

Sliver (and most other modern post-exploitation frameworks) can change the credentials cached in LSASS. Sliver does this by using the make-token command. This uses the LogonUser Windows API function with the dwLogonType LOGON32_LOGON_NEW_CREDENTIALS, which Microsoft describes as:

The new logon session has the same local identifier but uses different credentials for other network connections This means local access decisions are determined by the access token, but access to remote computers is determined by the new credentials in LSASS.

I’ll often refer to these types of logons as “Network Only”, since:

- The new credentials are only used during network authentication

- The

runas.execommand allows you to perform this logon with the/netonlyflag

This type of access token manipulation is beneficial to an attacker because:

- An attacker doesn’t need to launch a new process as another user to perform network activity as that user. The attacker can continue using their same implant process

- There’s less activity in logs, which makes forensic work more difficult. Depending on how the network only logon is performed, there might not be any evidence in logon events that links the Network Only logon to the malicious process (for example, certain logon Windows API calls will show the logon being created by the Secondary Logon (seclogon) service rather than the malicious implant that requested the logon)

Detecting access token abuse

… is hard.

Native logs that are generated during access token manipulation are high noise. Additionally, most logging mechanisms don’t/can’t provide the insight into why an access token was modified. Even if a SOC collects logs to identify anomalous token activity, it’s typically not trivial to determine if a token modification is expected for a process or anomalous without lots of baselining.

Detecting access token theft

A common use case for token theft is stealing a SYSTEM token from winlogon.exe to elevate from a local administrator to SYSTEM. To detect it, this post from SpecterOps recommends running the following commands (requires James Forshaw’s NtObjectManager):

auditpol /set /category:"Object Access" /success:enable /failure:enable

$p = Get-NtProcess -name winlogon.exe -Access GenericAll,AccessSystemSecurity

Set-NtSecurityDescriptor $p “S:(AU;SAFA;0x1400;;;WD)” Sacl

This command enables success and failure auditing policies from the “Object Access” category. This alone is untenable for most SOCs given the extremely high volume of logs that come from this auditing policy, not to mention that the detection also requires additional configuration on every endpoint to enable auditing of winlogon.exe. All this “detection” tells you is that a process requested access to winlogon.exe with PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION OR PROCESS_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATION (you can log the same data with Sysmon’s ProcessAccess event (Event ID 10)) - it doesn’t tell you that winlogon.exe’s access token was stolen. A potential improvement here might be to only look at these events if the source process (the one requesting access to winlogon.exe) is uncommon or has never been seen in your environment. I still suspect that this detection would remain relatively noisy.

To see if there is an alternative signal for access token manipulation, I enabled all native security auditing logs using auditpol /set /category:* /success:enable and ran Sliver’s impersonate command on a test machine with Defender XDR. For this activity:

- No native Windows security logs are generated

- No Defender XDR alerts are generated

- No events are generated in the Advanced Hunting portal for Defender

- No events are generated in the Device Timeline for the test machine in Defender

Sliver uses syscalls to bypass some userland EDR hooking, which I thought might be interfering with the log generation. I wrote my own C code for testing access token theft and it too generated no practical logs suitable for a detection.

You might be able to create a detection for a process created event (either via Sysmon or native Windows auditing capabilities) where the parent username is SYSTEM and the current username is a domain user, but I suspect the detection would be difficult to maintain due to the high volume of legitimate use cases. For example, the task scheduler service runs as SYSTEM, but may launch child processes running as domain users. Your SOC will thank you for not implementing this detection.

With the tools I have available, there are no high fidelity detections for access token theft.

Detecting cached credential changes

In its most basic form, you could engineer a naive detection for NewCredentials logons by simply looking for Windows Security Event ID 4624 (An account was successfully logged on) with a Logon Type of 9 (NewCredentials). Here’s an example log, modified from UltimateWindowSecurity:

An account was successfully logged on.

Subject:

Security ID: Domain\user01

Account Name: user01

Account Domain: Domain

Logon ID: 0x3E7

Logon Information:

Logon Type: 9

Restricted Admin Mode: -

Virtual Account: No

Elevated Token: No

Impersonation Level: Impersonation

New Logon:

Security ID: Domain\user01

Account Name: user01

Account Domain: Domain

Logon ID: 0xFD5113F

Linked Logon ID: 0x0

Network Account Name: adminuser01

Network Account Domain: ExternalDomain

Logon GUID: {00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000}

Process Information:

Process ID: 0x30c

Process Name: C:\Users\user01\example.exe

Network Information:

Workstation Name: -

Source Network Address: -

Source Port: -

Detailed Authentication Information:

Logon Process: Advapi

Authentication Package: Negotiate

Transited Services: -

Package Name (NTLM only): -

Key Length: 0

The typical activity I’ve seen from these logon events:

- IT admins using a tool or utility (such as runas.exe) to authenticate over the network as their admin account either in the same domain or in a different, trusted domain. For example:

runas.exe /user:ExternalDomain\admin01 /netonly mybinary.exe - The IIS worker process will also use this logon type to impersonate domain users.

A simplistic detection, which would ignore potential malicious activity by tuning out the common false positives mentioned above, could be written as the following Sigma rule:

title: Windows Network Only Logon

id: 8f1ec2e0-64c4-43e9-a5f5-90f76c852553

status: experimental

description: Detects a network only logon which could be indicative of an attacker adding new credentials to their malware for the purposes of lateral movement

references:

- https://trdan6577.github.io/Windows-Access-Tokens/

tags:

- attack.privilege_escalation

- attack.t1134

author: Tom Daniels

date: 2024/01/16

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

selection:

EventId: 4624

LogonType: 9

issworkerprocess:

ProcessName: 'C:\Windows\System32\inetsrv\w3wp.exe'

sameuser:

NetworkAccountName|fieldref: 'AccountName'

condition: selection and not issworkerprocess and not sameuser

fields:

- fields in the log source that are important to investigate further

falsepositives:

- Administrative users using runas.exe with the /netonly flag for a different domain

- Regular users performing a network only logon with their administrator account. Unfortunately, Sigma detection logic does not provide a way to tune this out without tuning out all NetworkAccountNames that begin with "admin"

level: medium

With some baselining for your specific environment, this rule could become high fidelity since logon type 9 is uncommon compared to the other logon types.

Bonus Access Token Abuse

Custom token theft program

I wrote some c code to perform token theft! You can view it here

External article

One final interesting token abuse example: the Elastic security team put out a blog post in 2023 detailing an attack on Windows Defender by abusing access tokens. Access tokens are, themselves, securable objects. The permissions on the access token for Windows Defender (at the time the article was written) allowed any other process that was running as SYSTEM to gain full control over the token. They used this full control to lower the integrity level of the token to untrusted which blocked Defender from taking action on any malicious file with an integrity level greater than untrusted.

You can read more about their research here.

References

The references not listed in-line are:

- Windows Internals, Part 1. 7th edition

- Programming Windows Security by Keith Brown

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/secauthz/impersonation-tokens

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/windows/it-pro/windows-server-2003/cc758849(v=ws.10)

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/4686897/sessions-window-stations-and-desktops

- https://learn.microsoft.com/pt-pt/previous-versions/windows/server/cc783557(v=ws.10)?redirectedfrom=MSDN#access-tokens-processes-and-interactions

- https://www.elastic.co/blog/introduction-to-windows-tokens-for-security-practitioners

- https://www.elastic.co/blog/how-attackers-abuse-access-token-manipulation

- https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/event.aspx?eventID=4624

Leave a comment