Thinking With Portals

Introduction

This past month, I had an international flight that left out of the JFK Airport in New York City. After arriving at the airport and standing in various lines for what felt like hours, I made it to my gate just as the flight started boarding. Great, another line. Unlike the mob of people that suddenly stood up and rushed to the gate entrance, I decided to take a seat and wait for the line to die down before heading to the gate. I connected to the open wireless network that the airport provided and was prompted by Firefox to “Sign in to use this network”. I’m not exposed to captive portals at $dayjob, have no prior experience working with them, and have no idea how they’re used. No better time to figure it out than on a 9 hour flight! All I had time to do was take a packet capture so the analysis that follows has some unanswered questions.

What Is A Captive Portal?

A captive portal is a web page that a user must interact with in order to use the network they’re connected to. They can be used to enforce one or more of the following:

- Ensure the end user agrees to the terms and conditions of the provider’s network before accessing the Internet

- Monetizing access to the Internet, either through forcing users to pay money to browse the web or requiring users enter their personal information (name, phone number, email address, etc). Captive portals can then track a user’s browsing activity (similar to how an ISP might track a user’s activity) and sell the information gathered to an advertiser.

- Control the bandwidth of each device on the network

JFK’s Captive Portal

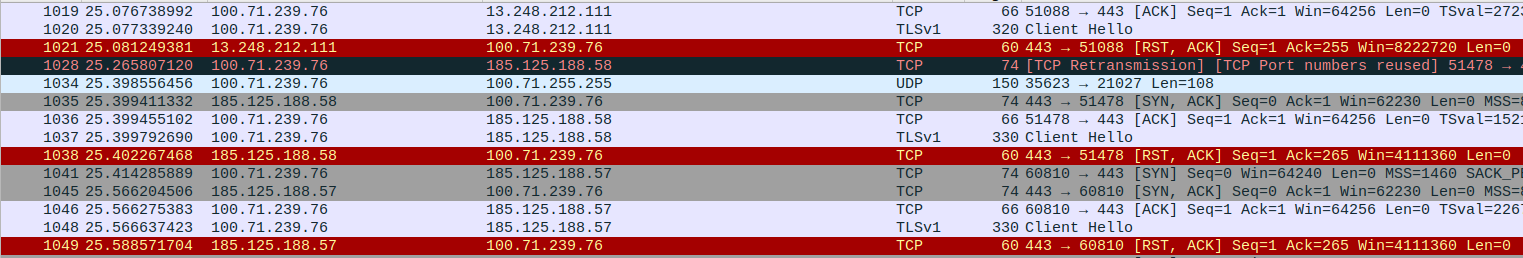

The first thing that stands out to me in the packet capture is all of the RSTs! It’s difficult to miss the bright red coloring Wireshark uses for them 😉. Nearly all of the RSTs are sent in response to my laptop’s (100.71.239.76) Client Hello message in each TLS handshake that it tries to initiate.

We’ll come back to the RSTs in a bit.

When I search for the name of the captive portal (via.boingohotspot.net), the first result that I is:

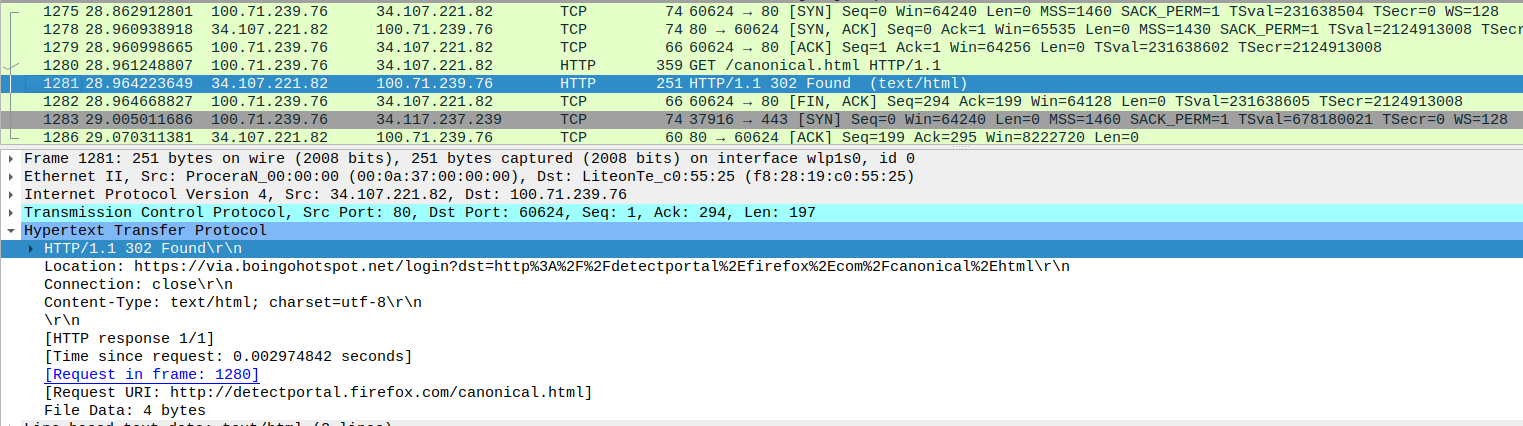

where 34.107.239.76 is the web server for detectportal.firefox.com. The 302 response I’ve highlighted seems highly unusual. How would Mozilla know to redirect me to the captive portal? Why wasn’t I sent an RST in response to my connection to the web server?

Taking a look packets in that TCP stream, there’s a very slight discrepancy between the default gateway’s MAC address in the initial SYN segment and default gateway’s MAC address in the HTTP redirect. The VMware MAC address, 00:50:56:90:42:ce, appears in most of the network communication with IP addresses outside of the subnet (including the HTTP GET request), whereas the ProceraN MAC address, 00:0a:37:00:00:00, appears in the HTTP redirect and all of the RSTs. This ProceraN device is blocking legitimate responses and spoofing RST packets from external IP addresses to terminate network communications.

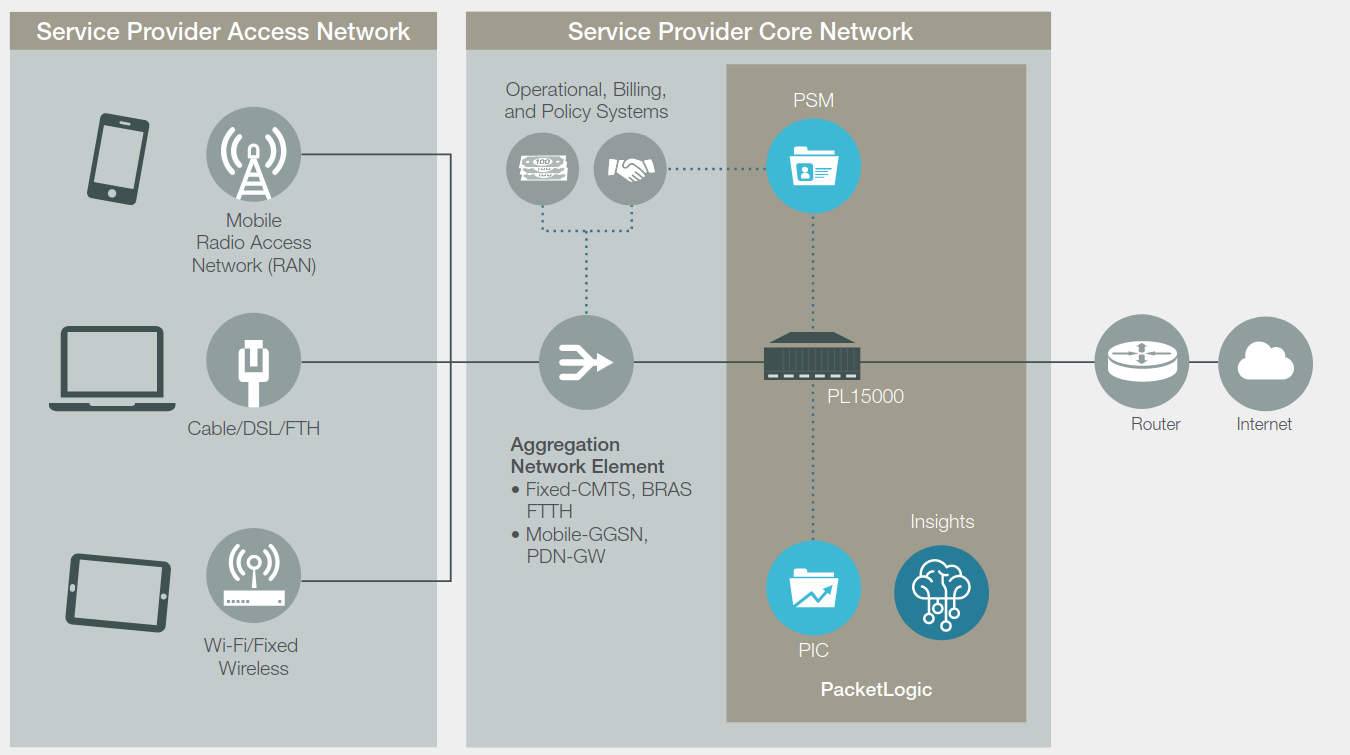

But what’s ProceraN? Procera Networks was a networking equipment company specializing in deep packet inspection technologies. According to an old PDF, Procera Networks used to have a product called “PacketLogic Intelligent Policy Enforcement” which included a captive portal. Procera Networks was eventually accquired by Sandvine in 2017. Sandvine still has the PacketLogic platform.

Putting all of our breadcrumbs together, it appears that the Procera Network’s MAC address is the captive portal that’s preventing us from accessing the Internet without first signing in. It’s spoofing HTTP responses from external IP addresses and responding with redirect requests to the captive portal web page. Firefox is seeing the 302 redirect and notifying the user that a captive portal exists. Once the user agrees to the terms and conditions of the network, communication to the Internet is allowed.

Another Type of Captive Portal

JFK airport’s captive portal sends HTTP redirects to get users to the landing page, but there’s another way to implement a captive portal. Captive portals can function by only allowing connectivity to the local DNS resolver on the network. The local DNS resolvers will return the IP address of the captive portal for any DNS request made by a client until registers their device in the captive portal.

A problem with this type of captive portal is HTTPS and HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS). If I type https://www.google.com/ into my browser’s search bar while behind this type of captive portal, I’m given the IP address of the captive portal. When my browser opens an HTTPS connection with the captive portal (thinking that it’s Google’s web server), the captive portal’s certificate will fail validation as the certificate isn’t valid for www.google.com. I can ignore the security warning (bad practice for users to engage in), but only if HSTS is disabled. The good news is that most browsers are able to detect these types of captive portals and will prompt users to visit the portal page before a user gets the certificate warning.

I’ll discuss this type of captive portal more later on.

Outstanding Unanswered Questions

A list of questions that I can’t accurately answer without getting back on the airport wifi:

- How did the captive portal know that I hadn’t yet agreed to the terms and conditions? My best guess This was likely done based off of MAC address (or IP address). The captive portal keeps track of MAC addresses that have agreed to the terms and conditions in a database or list. If a device tries to access the Internet with a MAC address that isn’t in the list, the captive portal blocks the connection.

- If I return to the airport and re-connect to their wireless system, will I have to agree to the terms and conditions again? In other words: Is my agreement only valid for a fixed time limit? I don’t have an answer for this. I suspect there’s a timeout but have no proof. At the very least, it would make sense to have a timeout so that users would be required to visit the captive portal again if JFK’s lawyers decided the terms and conditions needed an update.

- In technical terms, how would a network administrator set up the captive portal? Taking a look at the datasheet for the Sandvine PacketLogic 15000, it appears the captive portal sits inline between the clients and the router, inspecting traffic as it goes by. All traffic destined for the default gateway first passes through the captive portal.

Potential Captive Portal Bypasses

The following are untested (by me) ways to bypass this captive portal and potential detections for those bypasses

MAC Spoofing

Assuming that the captive portal allows access to the Internet based on MAC address, a nefarious user could simply use a tool like macchanger to change the MAC address of their wireless NIC to that of an authenticated user. The malicious actor’s only prerequisite would be to identify which MAC addresses were already authentiated by performing a packet capture on the wireless network. The devices with active TLS sessions to external IP addresses should be authenticated.

This would be fairly trival to detect. If there are two IP addresses associated with one MAC address, MAC spoofing is likely occurring. The easiest way to detect this would be with DHCP logs, though this detection method wouldn’t be effective if the malicious actor set their IP address statically. A better (albiet more difficult to implement) method could be to use something like Zeek, previously known as Bro, to include MAC addresses in the logs. This is assuming the captive portal doesn’t already log client MAC addresses as part of the analytics they provide.

DNS tunneling

Iodine is software that allows you to tunnel IPv4 data through a DNS server. If the captive portal allows you to make DNS requests, you own a domain name, and you have a publicly accessible server, you can create a DNS tunnel to bypass the captive portal. At a very high level, the server (publicly accessible DNS server) has iodine listening on port 53. Once the client has authenticated to the server, traffic flows over the channel as DNS requests for <encodeddata>.mydomain.com. Note that are there a number of alternative DNS tunneling tools available such as dnscat2.

You could detect the tunnel by using one or more of the following methods:

- X or more DNS requests from a client for a subdomain with the same parent domain within Y minutes (that’s a mouthfull)

- X or more DNS requests from a client within Y minutes

- DNS request with a subdomain longer than X characters

Although I haven’t experimented with it myself, Zeek has a DNS module that could likely log the information needed to detect these.

Security Considerations For Captive Portal Detection

If captive portal detection is done via HTTP, what’s stopping a nefarious actor from inserting their own 302s? This could be done over a wireless network even if there are no captive portals on the network, as the browser sends these out every once in a while to see if there’s a captive portal.

An impractical solution to this problem might be for all captive portals to use the DNS method for captive portals that I described earlier. A better solution might be RFC 8910 which proposes a DHCP option to inform clients that there’s a captive portal they need to interact with in order to access the Internet. Currently, the status of this RFC is “Proposed” and is not an “Internet Standard”.

Leave a comment