How “Remember Me” Works In Game Clients

Introduction

I recently need to re-authenticate to Blizzard’s Battle.net client and it got me wondering how game clients remember passwords for users. I already know how passwords are “remembered” for various websites while browsing the web using Chrome or Firefox: 🍪. The short explaination is that passwords generally aren’t remembered. Once you’re authenticated to a server, it returns a token (usually in the form of a cookie) that you can use to prove your identity to the server. That cookie can be saved to your local computer and used again, even after your computer restarts, provided the cookie hasn’t expired. There’s some good information on cookies on this StackOverflow post. Now, my goal is to figure out how the Battle.net client “Keeps me logged in”.

The writeup I made for this is a bit lengthy so I created an abbreviated version of the post in the summary section below. If you want to understand how exactly I went about researching Battle.net to understand how I stayed logged in, click here! There’s also a bonus section (bonus sections are supposed to be longer than the main article, rigt?) on how I went from an encryption key registry location to writing a decryptor for a sqlite database just after that.

Summary

I started my analysis by firing up Procmon, then logging into the Battle.net client and browsing through the results. After a bit of filtering and scrolling, one of the interesting locations I found on disk was

- C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\CachedData.db

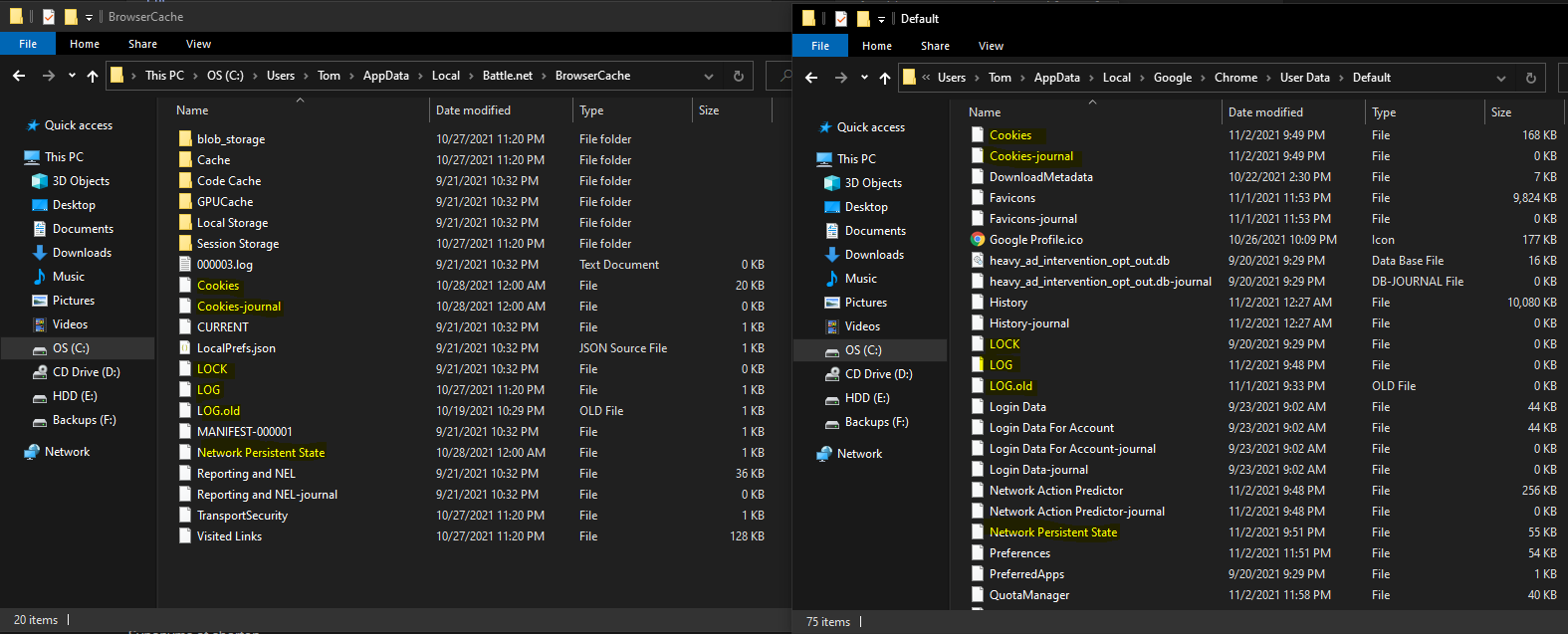

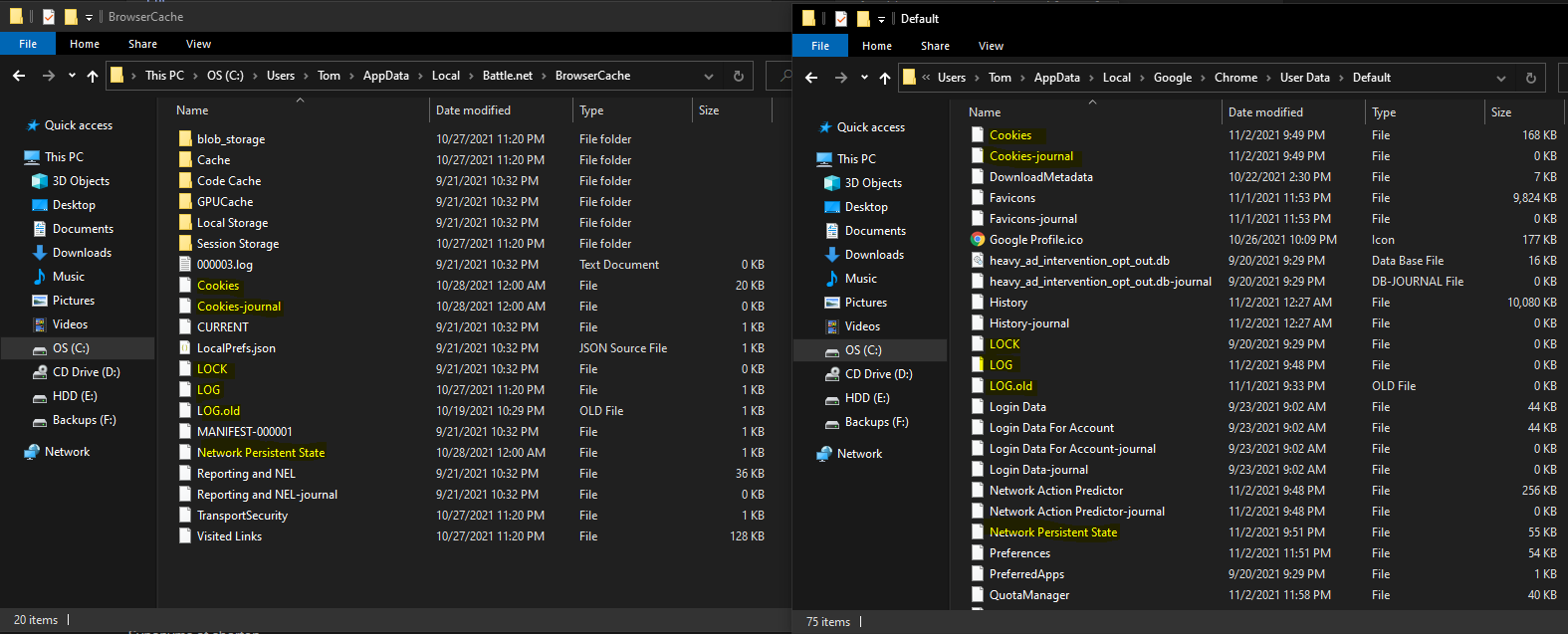

While this SQLite database didn’t contain any interesting authentication data, I noticed there was a striking similarity between the file and folder names in C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\BrowserCache:

The cookies file in the Battle.net AppData directory is also a SQLite file with the same structure as Chrome’s cookie file. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, I guess. The authentication cookies can be decrypted the same exact way Chrome’s cookies can be decrypted. There are plenty of open source Chrome cookie extraction tools that you can modify to work with Battle.net if you’re looking to automate extraction.

Due to the lack of real sustenance of a post that ends with “yea it’s exactly the same as chrome cookies” and my own personal curiousity, I decided to look into the other interesting string present in the ProcMon results, namely:

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Blizzard Entertainment\Battle.net\EncryptionKey\CacheDatabase

The key is encrypted with the DPAPI and optional entropy that’s hard coded into the Battle.net binary. More info on how I discovered all of this can be found in the deep dive.

The final interesting string was from the ProcMon results was:

- C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\Account\123456789\account.db

I couldn’t analyze this file as-is because it was encrypted. Digging through documentation for different SQLite encryption tools, I eventually found similarities between the account.db file, what was described in the SQLite Encryption Extension (SEE), and how the data was being decrypted in the debugger I was using. I didn’t know of any open source SEE decryption tool, so I wrote one to decrypt the account.db file using the information on the SEE documentation page and the encryption key found in the registry. The only interesting data contained in the database appeared to be an OAuth token.

Deep Dive: How I Stay Logged In

As with all simple questions, I started with a Google search to see if the answer was already out there. Most of the results I found related to people who forgot their passwords and were trying to recover it - I couldn’t find anything describing the technical tidbits of how and where a game client stores that information.

Let’s dive in! I was looking to analyze this on Windows, so I started by firing up Procmon, then logging into the Battle.net client and browsing through the results. After a bit of filtering and scrolling, I found a couple of interesting locations on disk:

- C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\Account\123456789\account.db

- C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\CachedData.db

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Blizzard Entertainment\Battle.net\EncryptionKey\CacheDatabase

I’ll take a look at one I think might require the least work first: the account.db file. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to determine the file type based on the file magic and I don’t see any patterns in the hex which makes me think this file is encrypted or encoded.

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 50 58 18 80 EA 27 B9 03 C5 3F 36 DB 87 F7 25 22 PX.ê'¹.Å?6Û÷%"

00000010 10 00 01 01 0C 40 20 20 46 54 AB 70 D1 EB C4 0C .....@ FT«pÑëÄ.

00000020 1F 5F 55 F9 1E D1 7C C9 32 FB D6 F4 CC 91 EE 8B ._Uù.Ñ|É2ûÖôÌî

00000030 25 BD B1 8B 4D 4F A3 2E 95 3F 6D 89 84 15 E0 AB %½±MO£.?m.à«

00000040 01 86 A5 E3 FB FD 1F A4 D2 39 DB C6 50 04 25 83 .¥ãûý.¤Ò9ÛÆP.%

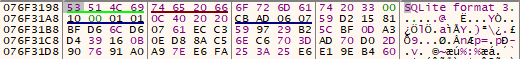

Alright, next on the “quick win” list is CahedData.db and it looks like a SQLite database:

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 53 51 4C 69 74 65 20 66 6F 72 6D 61 74 20 33 00 SQLite format 3.

00000010 10 00 01 01 00 40 20 20 00 00 00 68 00 00 00 10 .....@ ...h....

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 04 ................

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 ................

Here’s the schema from database:

SELECT * FROM sqlite_schema WHERE type = 'table';

| type | name | tbl_name | rootpage | sql |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| table | schema_info | schema_info | 2 | CREATE TABLE schema_info (table_name TEXT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL, version INTEGER DEFAULT 1) |

| table | login_cache | login_cache | 4 | CREATE TABLE login_cache (name TEXT NOT NULL, environment TEXT NOT NULL, battle_tag TEXT NOT NULL, account_id_hi INT NOT NULL, account_id_lo INT NOT NULL, connected_environments TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT ‘’, UNIQUE(account_id_hi, account_id_lo, environment) ON CONFLICT REPLACE) |

| table | remote_objects | remote_objects | 6 | CREATE TABLE remote_objects (url TEXT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL, content BLOB, content_hash TEXT NOT NULL, dismissed INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0, last_seen_time DATE, type INTEGER) |

| table | catalog_cache | catalog_cache | 8 | CREATE TABLE catalog_cache (component TEXT NOT NULL, version INTEGER NOT NULL, digest_hash TEXT, signature_hash TEXT, UNIQUE(component, version) ON CONFLICT REPLACE) |

| table | browser_stats | browser_stats | 10 | CREATE TABLE browser_stats (browser_name TEXT NOT NULL UNIQUE, count_load_start INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_load_end_ok INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_load_end_ng INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_load_error INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_render_abnormal INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_render_killed INTEGER DEFAULT 0, count_render_crashed INTEGER DEFAULT 0, PRIMARY KEY(browser_name)) |

| table | announcements | announcements | 12 | CREATE TABLE announcements (id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL, game TEXT NOT NULL, first_display_time DATE, dismissed INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0, expired INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0, seen INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0) |

| table | key_value_store | key_value_store | 13 | CREATE TABLE key_value_store (key TEXT NOT NULL, value TEXT NOT NULL, UNIQUE(key) ON CONFLICT REPLACE) |

| table | personal_avatar | personal_avatar | 15 | CREATE TABLE personal_avatar (region TEXT NOT NULL, file_id TEXT NOT NULL, contents_hash TEXT NOT NULL, last_updated INTEGER, max_age INTEGER, last_modified INTEGER, category INTEGER DEFAULT 0, PRIMARY KEY(region,file_id)) |

The first table of interest is login_cache, but it doesn’t contain any useful information:

SELECT * FROM login_cache;

| name | environment | battle_tag | account_id_hi | account_id_lo | connected_environments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72705XXXXX | us.actual.battle.net | Cargo#XXXX | XXXXXXXXXXXXX | XXXXXX | EU,KR,SG,US,XX |

It also doesn’t look like our EncryptionKey registry value (CacheDatabase which seems related to this file based on similarities between the names) could be used here because there don’t appear to be any encrypted fields in this database.

Interestingly enough, the file structure of C:\Users\Tom\AppData\Local\Battle.net\BrowserCache\ look somewhat similar to the file structure for Google Chrome:

Perhaps the cookie(s) used for authentication are stored here too! We even have the cookies file at in the BrowserCache directory. We’re able to successfully open the file as a SQLite database and we have table that looks like the cookies table that Chrome uses:

SELECT * FROM cookies;

| creation_utc | host_key | name | value | path | expires_utc | is_secure | is_httponly | last_access_utc | has_expires | is_persistent | priority | encrypted_value | samesite | source_scheme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13276751562890058 | .battle.net | bnet.extra | /login | 15424235209890058 | 1 | 1 | 13278997798167785 | 1 | 1 | 1 | blob | 0 | 2 | |

| 13276751541427312 | .battle.net | web.id | / | 15424235188427312 | 1 | 1 | 13278997798001951 | 1 | 1 | 1 | blob | 0 | 2 |

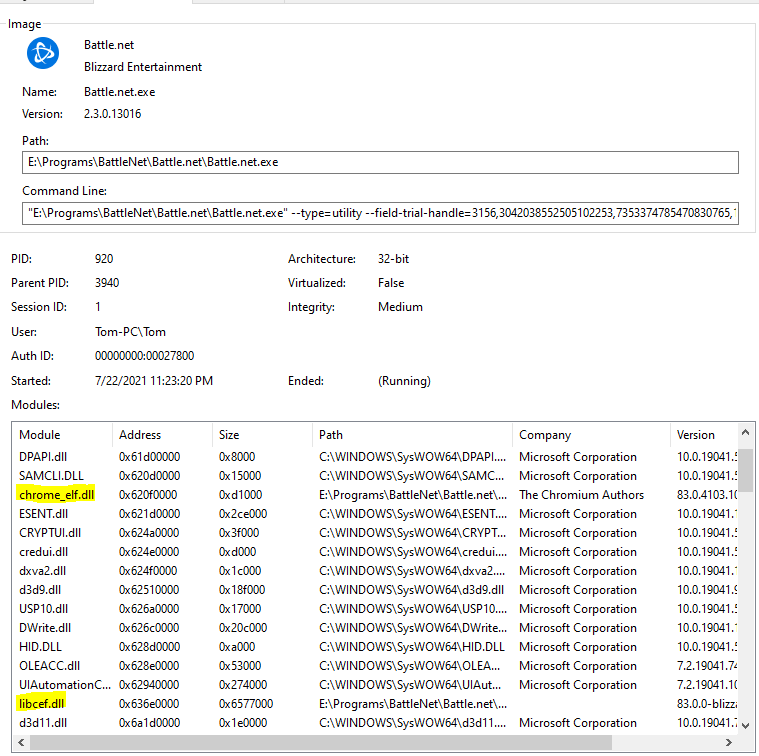

We can even confirm that Battle.net is using Chromium libraries as Procmon provides a list of modules loaded by the process:

We can see both chrome_elf.dll and libcef.dll show up in the list of loaded modules. Straight from the libcef github page: “Chromium Embedded Framework (CEF) official mirror. A simple framework for embedding Chromium-based browsers in other applications.” At this point, it’s pretty likely Battle.net uses Chromium libraries on it’s backend for authentication.

Now, if you haven’t kept up on your cookie game like I hadn’t, you can feel free to join me at the Table of Misery™. Chromium changed the way cookies are stored in Windows starting in Chromium version 80. Before version 80, the encrypted value field in the Cookies SQLite file could simply be decrypted by the currently logged on user via the DPAPI and a call to CryptUnprotectData.

With the advent of Chromium version 80, cookies are encrypted using the AES256-GCM algorithm, the key and initialization vector (IV) for which are encrypted with the DPAPI, base64 encoded, and stored in a json file called “local_state” (this is actually called “LocalPrefs.json in the Battle.net directory). You can differentiate between cookies encrypted with both methods by looking at the 3 byte prefix of the encrypted cookie value. If it’s prefixed with v10 or v11, it uses the newer encryption method (Chromium 80+), otherwise, it uses the older encryption method. There’s a great analysis of how Chromium does this here.

Initially, I was unaware of this new change and tried to decrypt the cookie value using the older method. When it failed, I assumed that the battle.net client simply used a slightly different method of encryption to store the cookie values and moved on to figuring out what the encryption key in the registry was used for, which we’ll cover in the next section.

There’s tons of open source code for extracting chrome cookies so no point re-inventing the wheel for a slightly different file path. I’ve been working a lot with PowerShell recently, so I found James O’Niell’s writeup for extracting cookies via PowerShell really handy. Anyway, the answer to our original question “How does Battle.net keep me logged in?” is by utilizing Chromium’s code base and using locally stored cookies for authentication.

Deep Dive: Encryption Key Analysis

Let’s take a look at the mysterious encryption key now:

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 01 00 00 00 D0 8C 9D DF 01 15 D1 11 8C 7A 00 C0 ....Ðß..Ñ.z.À

00000010 4F C2 97 EB 01 00 00 00 59 F6 D7 B5 6C A6 07 46 OÂë....Yö×µl¦.F

00000020 97 A8 97 8D DE 9C 5D C5 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 ¨Þ]Å........

00000030 00 00 10 66 00 00 00 01 00 00 20 00 00 00 F0 D7 ...f...... ...ð×

00000040 33 AF EA D0 93 28 72 81 6F 40 DC 5B 57 BD 2C 22 3¯êÐ(ro@Ü[W½,"

00000050 F6 18 E6 BF 9F 23 10 9A 4E AE F9 84 89 E6 00 00 ö.æ¿#.N®ùæ..

00000060 00 00 0E 80 00 00 00 02 00 00 20 00 00 00 D6 D5 ......... ...ÖÕ

00000070 86 A3 5B 76 83 91 39 79 31 D2 1F A1 8A 73 01 5D £[v9y1Ò.¡s.]

00000080 9C 59 A8 EA 35 33 A0 D2 B7 C2 02 B3 4E EC 30 00 Y¨ê53 Ò·Â.³Nì0.

00000090 00 00 22 96 D9 A8 BF E7 5A B0 39 EB FD B2 51 02 .."Ù¨¿çZ°9ëý²Q.

000000A0 3F F1 0D 43 D5 64 D0 0B 15 C7 DC D3 AD 7F 65 9E ?ñ.CÕdÐ..ÇÜÓ⌂e

000000B0 2B 22 DC 73 EE 82 B0 A7 79 83 AE 3A 7A 78 0B A4 +"Üsî°§y®:zx.¤

000000C0 8C 28 40 00 00 00 B3 04 79 D1 21 A3 BD EA 8C 61 (@...³.yÑ!£½êa

000000D0 BD AB 48 39 8F 34 05 7C E3 D6 55 9A DF 95 36 5E ½«H94.|ãÖUß6^

000000E0 A6 62 E3 5D E6 BE 24 F3 64 7E D4 FF 3A 2A B1 B0 ¦bã]æ¾$ód~Ô.:*±°

000000F0 7C D6 94 D5 6B A5 6F 1E CC 5A CD 56 95 8B 4E 82 |ÖÕk¥o.ÌZÍVN

00000100 1B AF 07 83 51 6F .¯.Qo

At the time, this just looked like a big blob of data to me, though readers familiar with the DPAPI may have noticed the DPAPI header which indicates that the key is protected by the DPAPI. Not knowing that at the time, I moved on to see where this key was used in the Battle.net client by using x64dbg.

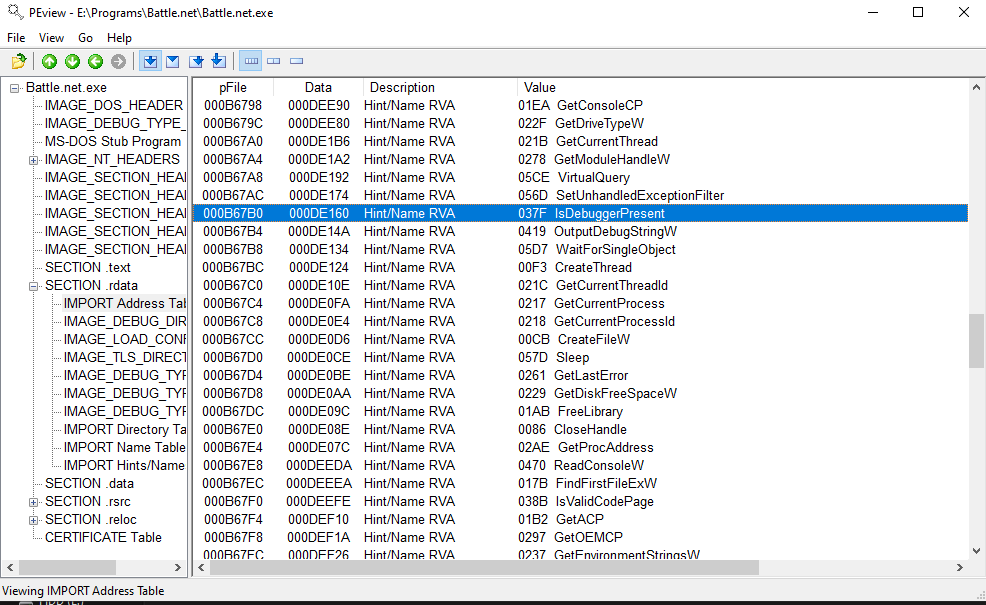

Battle.net won’t open if a debugger is attached to it - we can see in PEview that Battle.net imports the function IsDebuggerPresent.

Luckily, x64dbg provides a feature called “Hide debugger (PEB)”. There’s a great writeup on how this works here and some official x64dbg documentation here; the short of it is that IsDebuggerPresent checks a flag in the Process Environment Block to see if a debugger is attached to the process and x64dbg overwrites that value in the PEB, ensuring that it always returns false.

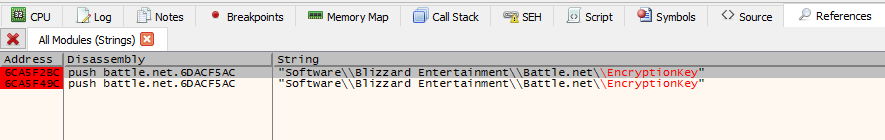

To verify all modules were loaded, I let Battle.net run until I was prompted for a username and password to log in, then used x64dbg’s search feature to search for the string “EncryptionKey”, found references to where our registry string was used, and set a breakpoint at both of those locations:

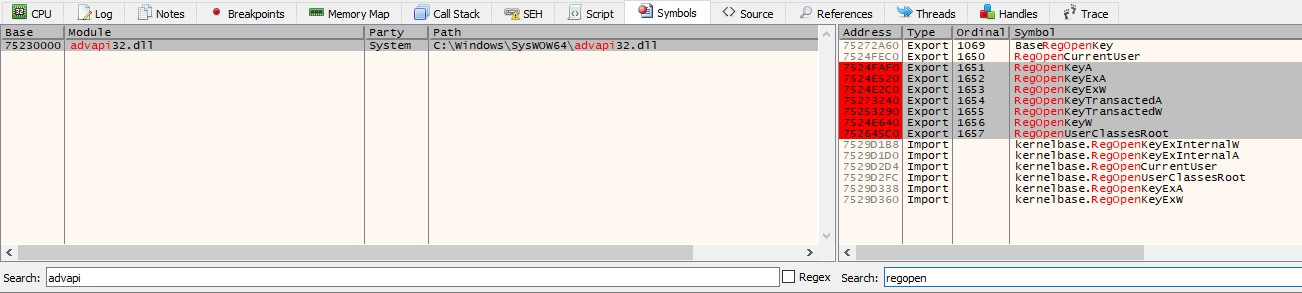

I restarted Battle.net and eventually hit the breakpoint I set after I entered my credentials for authentication. In order to read or write data to a registry location, we first need to obtain a handle to the registry key by calling one of the many forms of RegOpenKey (RegOpenKeyA, RegOpenKeyW, RegOpenKeyExA, you get the idea, there’s too many). To make our lives easer, let’s set a breakpoint at all of those functions and look for our encryption key string as one of the arguments. x64dbg allows you to set breakpoints at imported functions by searching for a module in the symbols tab and then filtering for the desired function:

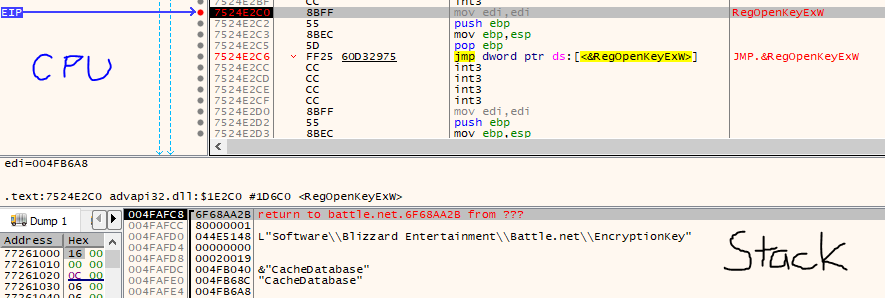

We slap that continue button in x64dbg and our first stop is in RegOpenKeyExW with the location of the encryption key registry string on the stack!

Using the stack and our handy MSDN page for RegOpenKeyExW, we can see that the call the RegOpenKeyExW looks a bit like:

RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_CURRENT_USER, // equivalent to 0x80000001 - http://www.jasinskionline.com/WindowsApi/ref/r/regopenkeyex.html

LPCWSTR encryptionKeyLocationString,

NULL,

KEY_READ, // equivalent to 0x20019 - https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/sysinfo/registry-key-security-and-access-rights

PHKEY futurePointerToHandleToKey);

Alright, we opened the key for reading but we haven’t read anything yet. Because it worked so well last time, let’s set a breakpoint at any registry key read functions (RegGetValue, RegQueryValueA, RegQueryValueExA, etc) just like we did for opening a registry key. Note that these functions take a handle to the registry key as one of their arguments so we need to follow futurePointerToHandleKey to obtain the value of our encryption key handle.

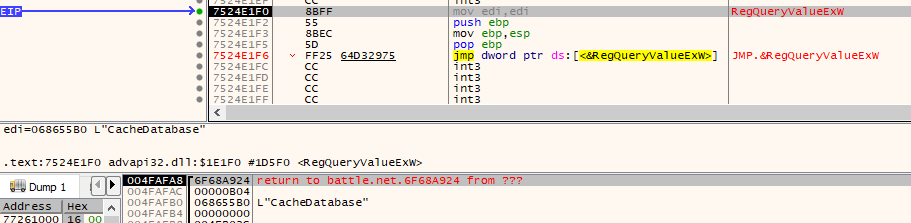

Again, we hit a breakpoint quickly and we can verify with the parameters on the stack that this function call is to read the data of the registry key value “CacheDatabase”:

What’s odd is that we don’t actually read the encryption key in this function call. If we step out of the call to RegQueryValueExW, we see an additional call to this function that actually reads and returns the value.

The first call checks to make sure the result of RegQueryValueExW is 0xEA or ERROR_MORE_DATA. Let’s set a breakpoint on the first byte of data returned from the registry query - pointed to by the 5th parameter in the function call - to see where it’s accessed.

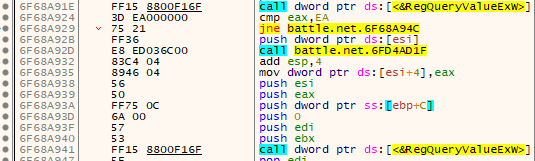

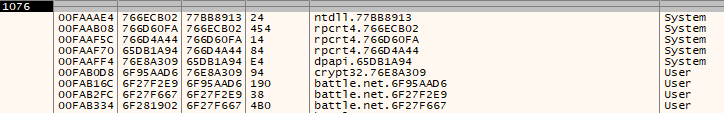

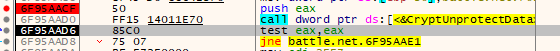

We end up stopping somewhere in ntdll.dll, as evidenced by all the well labeled jumps. By both using the “Execute till return” feature a few times and the Call Stack window, we can see that the registry value was used in a call to CryptUnprotectData, a function available in the DPAPI:

I set a breakpoint right above the call to CryptUnprotectData and restarted the program to see the arguments. The last parameter in the call is a pointer to an empty DATA_BLOB structure - this will store the size and location of the decrypted data once the function returns. If we follow it in the dump and step over the call to CryptUnprotectData, we can see the decrypted value:

61 65 73 32 35 36 3A ED E4 5A E3 58 AF 2E B3 A1 aes256:íäZãX¯.³¡

68 5B D9 5D D3 CC 65 7D E9 A0 92 98 75 F3 E7 F3 h[Ù]ÓÌe}é ..uóçó

Unsurpisingly, the value of our registry data is an AES encryption key! Try as I might, at this point I wasn’t able to figure out where this was used. I tried setting breakpoints on the first byte of this data, but all I found were instances of this key being copied - it was copied at least 3 times.

After a wide array of unsuccessful attempts to determine where this encryption key was used, I decided to try a different approach. From the initial investigation using ProcMon, we’re fairly certain that account.db is an encrypted SQLite database based off of the following:

- the non-uniformity of the data

- the .db file extension, which is shared by the known SQLite file CachedData.db

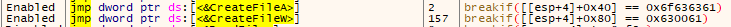

If we set a breakpoint at CreateFileA and CreateFileW looking for the path to account.db as the first argument, we can find the handle to account.db by inspecting the return value of CreateFile. Using that handle value, we can set a conditional breakpoint on ReadFile and ReadFileEx when account.db is read.

CreateFileA’s breakpoint hits if the characters at 0x40 in the file name are “acco” and CreateFileW’s breakpoint hits if the characters at 0x80 in the file name are “ac” (one character takes up two bytes in wide character sets).

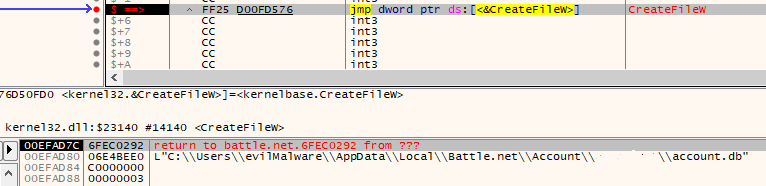

We hit our breakpoint! If we execute until return, we can see the value of the file handle in EAX, then set our condition breakpoint on the ReadFile calls:

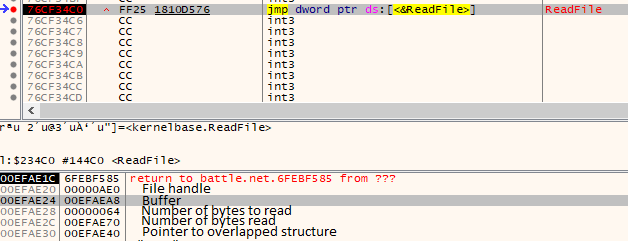

Then continue running the program until we hit the ReadFile breakpoint.

Let’s take note of the location of the buffer, execute until we return to get data in the buffer, then set a hardware breakpoint on the first byte of the buffer and continue the execution.

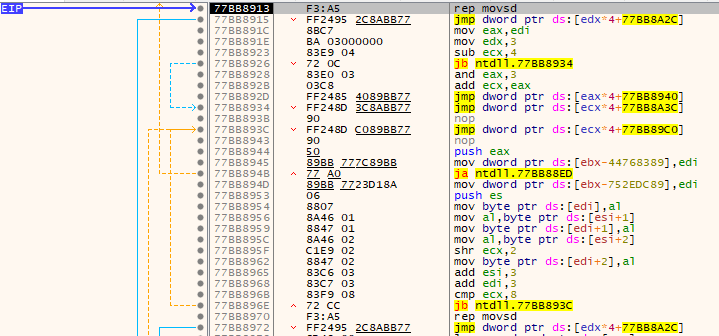

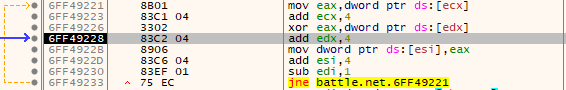

Our hardware breakpoint is hit here in this loop which looks like a simple XOR decryption routine! The data pointed to by EDX is the file we just read and ESI points to our destination buffer so all we have to do is figure out where the data pointed to by ECX comes from (*insert foreshadowing of lots of work here*). We confirm our suspicions by finishing a few loops of the decryption routine and looking at the data pointed to by ESI to see:

A couple things to point out here. First, the counter (contained in EDI) was set to 0x400. XORing 4 bytes at a time, this means that we only read and decrypted 0x1000 bytes of the file so there’s still more decryption to be done to view the rest of the encrypted database. Second, we know that there’s more to this decryption than just the XOR because the DPAPI decrypted key was prefixed with “aes256:”. Third, we know the file is a SQLite file. Can we find an existing open source tool that decrypts SQLite databases?

Our contenders:

- SQLCipher - open source SQLite encryption that uses AES-256

- SQLite Encryption Extension (SEE) - A paid licensed software extension developed by the same people that develop SQLite. This has pretty great documentation on how it works for software you need to license in order to use

- Dozens of open source github projects - fairly unlikely given the reliabiliy that a corporation like Blizzard would desire.

Decrypting with SQLCipher ultimately failed (I used DB Browser for SQLite), leaving us with the most likely option of SEE as the encryption method. Some interesting notes from the documentation page:

- Bytes 16 through 23 of the sqlite database header are unencrypted

- Each page is encrypted separately with a combination of the page number, random nonce, and the database key

- The encryption uses a 16 byte randomly choosen nonce on each page and a message authentication code

Let’s revist our hex dump of account.db:

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 50 58 18 80 EA 27 B9 03 C5 3F 36 DB 87 F7 25 22 PX.ê'¹.Å?6Û÷%"

00000010 10 00 01 01 0C 40 20 20 46 54 AB 70 D1 EB C4 0C .....@ FT«pÑëÄ.

If we parse bytes 16 - 23 using the header information, we get:

| Offset | Size | Header Description | Header Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 2 | Database page size | 0x1000 | Each page is 4096 bytes |

| 18 | 1 | File format write version | 0x1 | Legacy version |

| 19 | 1 | File format read version | 0x1 | Legacy version |

| 20 | 1 | Bytes of reversed space at the end of each page | 0xC | 12 bytes of space per page is reserved |

| 21 | 1 | Maximum embedded payload fraction. Must be 64 | 0x40 | 64 bytes |

| 22 | 1 | Minimum embedded payload fraction. Must be 32 | 0x20 | 32 bytes |

| 23 | 1 | Leaf payload fraction. Must be 32 | 0x20 | 32 bytes |

SQLite documentation lists 0x1000 as the default page size for a database. Based on how well these values map up to the expected values for a SQLite header, we found our encryption mechanism 😊. Unfortunately, there are no open source tools at my disposal to decrypt the file so I’ll have to write my own.

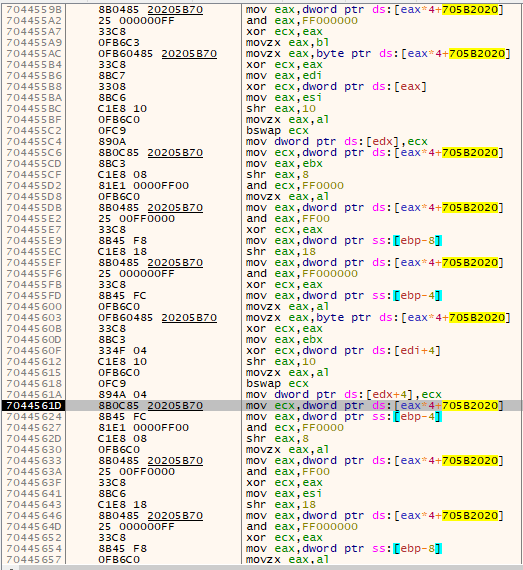

Back where we left off in the debugger, let’s set a memory breakpoint on the data used as the XOR key. After continuing, our debugger hits the memory breakpoint here:

Based on the leading “aes256” in our encryption key, the unusual lack of any conditionals in the above assembly function, and the Rijndael (AES) S-box at 0x705b2020 (referenced 9 times in the above image), this is the AES encryption routine!

705B2020 63 63 63 63 7C 7C 7C 7C 77 77 77 77 7B 7B 7B 7B cccc||||wwww{{{{

705B2030 F2 F2 F2 F2 6B 6B 6B 6B 6F 6F 6F 6F C5 C5 C5 C5 òòòòkkkkooooÅÅÅÅ

705B2040 30 30 30 30 01 01 01 01 67 67 67 67 2B 2B 2B 2B 0000....gggg++++

705B2050 FE FE FE FE D7 D7 D7 D7 AB AB AB AB 76 76 76 76 þþþþ×××׫«««vvvv

705B2060 CA CA CA CA 82 82 82 82 C9 C9 C9 C9 7D 7D 7D 7D ÊÊÊÊ....ÉÉÉÉ}}}}

705B2070 FA FA FA FA 59 59 59 59 47 47 47 47 F0 F0 F0 F0 úúúúYYYYGGGGðððð

705B2080 AD AD AD AD D4 D4 D4 D4 A2 A2 A2 A2 AF AF AF AF ....ÔÔÔÔ¢¢¢¢¯¯¯¯

705B2090 9C 9C 9C 9C A4 A4 A4 A4 72 72 72 72 C0 C0 C0 C0 ....¤¤¤¤rrrrÀÀÀÀ

705B20A0 B7 B7 B7 B7 FD FD FD FD 93 93 93 93 26 26 26 26 ····ýýýý....&&&&

At this point, we know the following:

- Cipher - this is AES-256 in CCM mode (Counter with Cipher block chaining Message authentication code mode) from the SEE documentation.

- Key - probably the one from the registry earlier but we haven’t confirmed this yet

We need to determine the following:

- What data is encrypted with AES to generate the XOR key?

- What is the IV/nonce used? We know from the SEE documentation that the nonce is present on each page in the database and is either 12 or 16 bytes (the documentation states “you can always check to see how much nonce is being used […] make sure it is being set to 4 or 12 or 32 and not zero” and “[…] with a 16-byte randomly choosen nonce on each page” 🤔)

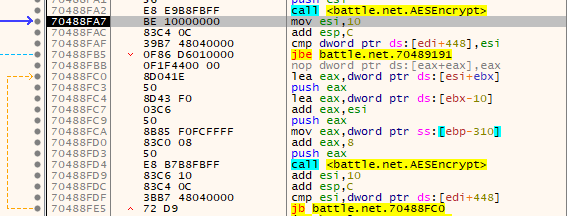

If we step out of the AES function (helpfully labeled “AESEncrypt” by yours truly), we can see that it’s called again just below in a for loop:

There are three arguments pushed on the stack before the function call. We’ll go through them in order of appearance:

- The first argument pushed onto the stack (

PUSHinstruction at0x70488FC3) is the buffer that receives the result of the encryption - The second argument pushed onto the stack (

PUSHinstruction at0x70488FC9) always points 0x10 bytes before argument 1. Each iteration of the loop moves this to point to the data we just encrypted. Based on how Cipher Block Chaining mode works (which is a component of CCM mode), the second argument is the IV - The final argument pushed onto the stack (

PUSHinstruction at0x70488fd3) points to our AES key from the registry! The only difference is that the “aes256:” is removed

If we set a breakpoint at the first call to the AESEncrypt function (0x70488FA2) and restart our debugger, we see that the initial IV is:

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

000000000 01 00 00 00 38 F3 05 F3 21 0E 9D 31 A8 05 8E 05 ....8ó.ó!..1¨...

Referencing the SQLite encryption documentation, “The key to encryption is a combination of the page number, the random nonce (if any) and the database key” and the “randomly choosen nonce [is] on each page”. Looking at the IV above, the first 4 bytes of data are 0x1, represented in little-endian. Because we just restarted our program and read the first page of the encrypted database, this is likely our page number. The next 12 bytes are the nonce and are present in our original encrypted account.db file as the last 12 bytes of the page:

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

000000FF0 3D BB CA 4F 38 F3 05 F3 21 0E 9D 31 A8 05 8E 05 =»ÊO8ó.ó!..1¨...

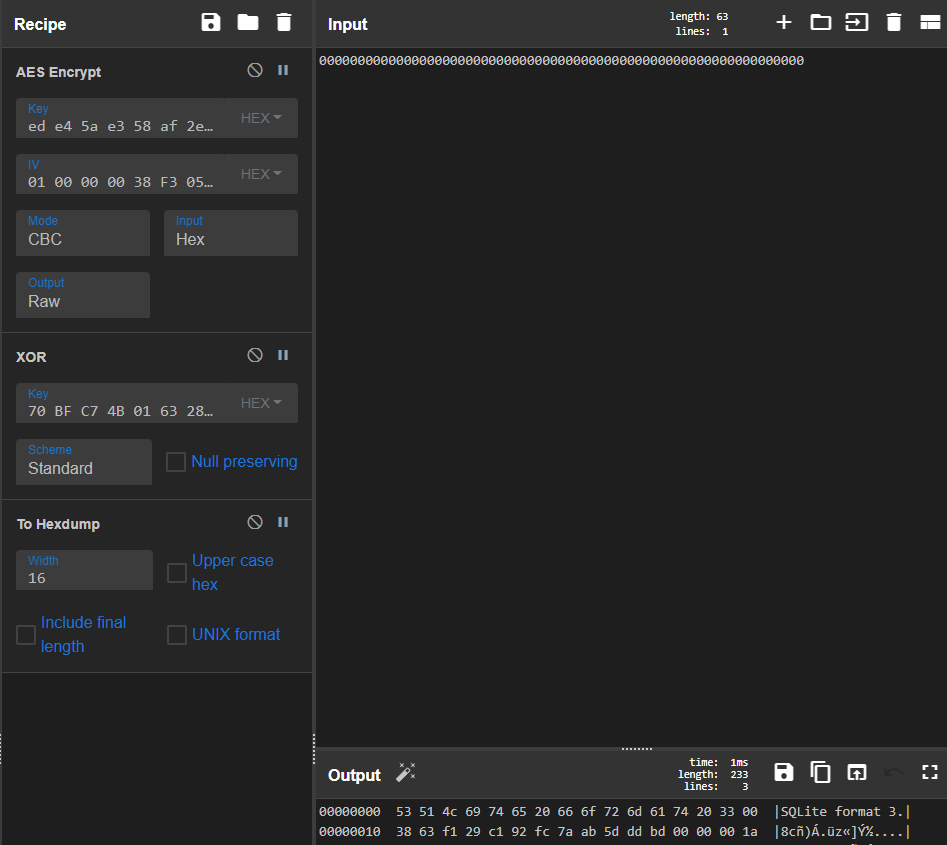

The only outstanding question we have is what data we’re encrypting to give us the XOR key. After searching around for a while, I couldn’t find anything obvious in the AESEncrypt file so, on a whim, I entered the key, IV, and all zeros for the data into cyberchef, followed by an XOR of the first 32 bytes of the encrypted account.db file:

*(cyber)Chef’s kiss* Viola! We have our decryption algorithm! Recall that bytes 16 through 23 are unencrypted in the original encrypted account.db file so they’ll need to be replaced in the output.

To simplify the process of decrypting the database, I wrote some Powershell code to do all the work for me:

Function Unprotect-BlizzardAccountDatabase {

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Decrypts Battle.net's account.db file.

.DESCRIPTION

Decrypts Battle.net's account.db file and places it on the current user's desktop.

Author: Tom Daniels

.EXAMPLE

C:\PS> Unprotect-BlizzardAccountDatabase

Decrypts the database and places it on the current user's desktop named decrypted.db

.EXAMPLE

C:\PS> Unprotect-BlizzardAccountDatabase -OutFile C:\Windows\Temp\decrypted.db

Decrypts the database, places it in C:\Windows\Temp and names it output.db

.LINK

https://trdan6577.github.io/

#>

[CmdletBinding()]

Param

(

[Parameter()]

[ValidateScript({Test-Path ($_ -replace '\\[^\\]*?$','\')})]

# The location to place the decrypted database

[String]$OutFile = "$env:USERPROFILE\Desktop\decrypted.db",

[Parameter()]

[ValidatePattern('\d+')]

# The account ID to decrypt the database for. Useful if you have more than one Blizzard account for some reason

[String]$AccountId

)

Write-Verbose "Validating setup parameters"

If (!$AccountId) {

Write-Debug "Attempting to automatically determine account ID"

# Validate the file location

If (!(Test-Path "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\")) { Throw "Couldn't find AppData folder for Battle.net. Is it installed?" }

If ((Get-ChildItem -LiteralPath "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\" -Directory).Count -ne 1) { Throw "Either no account ID or more than one account ID is located at $("$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\"). If more than one, please specify with -AccountId" }

$AccountId = (Get-ChildItem -LiteralPath "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\" -Directory).Name

Write-Debug "Automatically determined account ID of $AccountId"

}

# Make sure the account.db file exists

If (!(Test-Path "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\$AccountId\account.db")) { Throw "account.db file not present at $("$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\$AccountId\")" }

# Read the database as bytes and get the page size. Warn if the page size isn't the standard 4096 bytes

Write-Debug "Preping database variables"

$EncryptedDb = Get-Content -Path "$env:LOCALAPPDATA\Battle.net\Account\$AccountId\account.db" -Encoding Byte

$PageSize = ($EncryptedDb[16] * 256) + $EncryptedDb[17]

If (!($PageSize -eq 4096)) { Write-Warning "account.db has non-standard page size of $PageSize" }

# Get the database key

Write-Debug "Fetching and decrypting the key from the registry"

Add-Type -AssemblyName 'System.Security'

If (!(Test-Path 'HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Blizzard Entertainment\Battle.net\EncryptionKey\')) { Throw "Encryption key not found" }

$DPAPIProtectedKey = (Get-ItemProperty -Path 'HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Blizzard Entertainment\Battle.net\EncryptionKey\').CacheDatabase

$HardCodedOptionalEntropy = [Byte[]]@(0xc8, 0x76, 0xf4, 0xae, 0x4c, 0x95, 0x2e, 0xfe, 0xf2, 0xfa, 0x0f, 0x54, 0x19, 0xc0, 0x9c, 0x43)

$Key = [System.Security.Cryptography.ProtectedData]::Unprotect($DPAPIProtectedKey, $HardCodedOptionalEntropy, [System.Security.Cryptography.DataProtectionScope]::CurrentUser)

$Key = $Key[7..($Key.count - 1)] # Strip the leading "aes256:"

# Prepare the all zero array for encryption and the output byte array

Write-Debug "Preparing output variables"

$AllZeros = @(0x00) * $PageSize

$DecryptedDb = [Byte[]](@(0x00) * $EncryptedDb.Count)

Write-Verbose "Done validating setup parameters. Decrypting database and writing output to $OutFile"

For ($i = 0; $i -lt $EncryptedDb.Count; $i += $PageSize) {

# Set up AES cipher and encrypt _all_ the zeros!

$AesCipher = New-Object System.Security.Cryptography.AesCryptoServiceProvider

$AesCipher.Key = $Key

$AesCipher.IV = [byte[]]([byte[]]@((($i / 0x1000) + 1), 0x00, 0x00, 0x00) + [byte[]]$EncryptedDb[$($i+0x1000-0xC)..$($i+0x1000-0x1)])

$Encryptor = $AesCipher.CreateEncryptor()

$EncryptedBytes = $Encryptor.TransformFinalBlock($AllZeros, 0, $AllZeros.Length)

# XOR the encrypted database with the encrypted bytes to get plaintext

For($j = 0; $j -lt $EncryptedBytes.count; $j++) {

If (($i + $j) -ge $EncryptedDb.Count) { Break }

$DecryptedDb[$i+$j] = [byte]($EncryptedBytes[$j] -bxor $EncryptedDb[$i+$j])

}

# Clean up like a good programmer

$AesCipher.Dispose()

}

# Bytes 16 - 23 are unencrypted in the encrypted db: https://www.sqlite.org/see/doc/release/www/readme.wiki

Write-Debug "Replacing bytes 16 - 23 with their unencrypted equivalents"

For ($i = 16; $i -lt 24; $i++) { $DecryptedDb[$i] = [Byte]$EncryptedDb[$i] }

Write-Debug "Writing output file"

Set-Content -Path $OutFile -Value $DecryptedDb -Encoding Byte

Write-Verbose "Done decrypting. Output file written"

}

Here are the tables in the database:

| name |

|---|

| schema_info |

| account_storage |

| product_settings |

| product_group_settings |

| key_value_store |

| notifications |

| whisper_sessions |

| takeovers |

| facebook_bnet_friends |

| dismissals |

| suggested_friends |

| friends |

| friends_of_friends |

Most of these tables contain no data except for account_storage, key_value_store, product_group_settings, product_settings, and takeovers. The only data of interest that stood out to me was in key_value_store:

| key | value |

|---|---|

| api_gateway_access_token | OAuth Token removed from here |

| api_gateway_oauth_scopes | cts:read account.standard commerce.inventory.full account.standard:modify |

| last_selected_product_group | Pro |

| settings_telemetry_last_sent | 1635391236 |

| features_cached_data_points | {“account_country”:”USA”,”account_id”:XXXXXXXX,”account_region”:”US”,”geoip_country”:”US”,”licenses”:[274,16332,20010,20195,27639,37396]} |

Looks like there’s some sort of OAuth token present here! Maybe in a future blog post, I’ll figure out what it’s used for 😉

Leave a comment